Susan Foster of Clark University passed away recently. Here we collate and compile memories of some Susan's contributions to science, education, and collegiality. She will be sorely missed. This is a living document - please add your own thoughts in the comments.

1. In Remembrance of Susan Adlai Foster (1953 – 2021), ABS Fellow and Past President. Written by Matthew A. Wund, with input from John Baker, Christine Boake, Zuleyma Martinez, and Dale Stevens. This obituary is modified from text that will be published in the March newsletter of the Animal Behavior Society.

Dr. Susan Foster passed away at her home in Petersham, MA from complications associated with cancer on January 16, 2021. She was in the company of her loving husband, John Baker, and their two children, Patrick and Dylan. Susan devoted her career to the study of behavioral plasticity and evolution, and is best known for her extensive work using threespine stickleback fish as a model to understand these processes.

Susan earned her B.S. in Botany and Zoology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and in 1984, earned her Ph.D. in Zoology from the University of Washington under the mentorship of Robert T. Paine. Her graduate work investigated group foraging behavior in coral reef fish of Panama. She is most well-known for her extensive research on the plasticity and evolution of behavior in threespine stickleback fish. She began her stickleback research as a postdoctoral fellow working with Michael A. Bell at Stony Brook University. From 1990-1995, she continued this work as an Assistant Professor of Biology at the University of Arkansas. In 1995, she moved with her husband and collaborator, Dr. John Baker, to Clark University in Worcester, MA, where she spent the remainder of her career until her retirement in 2020. She continued mentoring her students and conducting research until her final days. Susan served Clark University with as much dedication and enthusiasm as she served the ABS, including in her position as the Warren Litsky Endowed Chair in Biology, and in her leadership on a variety of institution-wide committees and councils. She was also instrumental in establishing Clark University’s very successful Environmental Science Program, in which she served in several capacities.

Susan served the scientific community in many capacities throughout her career. She was exceptionally fond of the Animal Behavior Society, which spanned her nearly four decades of membership. The highlights of her service to the ABS include multiple terms as Secretary (1993-1999), Second President Elect (08-09), First President Elect (09-10), President (10-11), and Past-President (11-12). Susan was elected an ABS Fellow in 2004. More recently, she served as Executive Editor of Animal Behaviour, and served for more than a decade as the North American Editor of Ethology. Susan also served on numerous NSF review panels, and participated in several working groups sponsored by the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NEScent).

Susan’s body of work is exceptional for its breadth and depth. In more than sixty peer reviewed articles and book chapters, as well as four edited volumes, her research beautifully married natural history, extensive field observations, exquisite laboratory experiments, and evolutionary theory. She did not view herself as either a field biologist, or as an animal behaviorist, or as an evolutionary biologist, but rather as all of these things simultaneously. She had a wonderful ability to comprehend the interplay among multiple scales of biological organization: appreciating how the nuances of individual behavior related to complex evolutionary processes. She was fascinated by threespine stickleback fish as an individual species, while simultaneously leveraging their value as a model system for studying general processes of behavioral evolution and adaptive diversification.

In addition to her brilliant mind, Susan was a loving wife and mother, an exceptional cook, an avid gardener, and had a wonderful, dry sense of humor. She also had a lifelong interest in the conservation of natural landscapes, and while at Clark University taught a course on the topic nearly every year. She was an unwavering advocate for the many students and postdocs she mentored throughout her career, many of whom came to know her as not only a mentor and friend, but as a member of their family. Susan was perhaps most in her element in her 250-year-old farmhouse in Petersham, MA, where, with her husband John, she would effortlessly move between writing research papers and grants, reviewing manuscripts for Animal Behaviour and Ethology, gardening, cooking, and entertaining guests. While home was her happiest place, Susan also enjoyed traveling, spending many field seasons studying stickleback fish behavior in Alaska and British Columbia, and traveling to conferences around the world. Her life was enriched by the many friendships she formed in her travels and through her research; indeed, news of her passing has resulted in an outpouring of love and respect from friends across the globe.

To commemorate Susan’s life and legacy, and the impact she had on her friends and colleagues, her dear friend and fellow ABS Fellow Dr. Christine Boake shared these sentiments:

“Susan and I first met due to our mutual interests in behavioral divergence between animal populations, which we recognized could lead to speciation. Her generous hospitality made it easy for us to become close friends. Our visits always combined our shared interests in science, cooking, and gardening. She had boundless energy; even after surgery imposed physical limitations, she kept up a strenuous pace both in research and at home. Her energy and enthusiasm allowed her to have her noteworthy professional success as well as having a multifaceted and rewarding life with family and friends. She had a full life.”

Susan’s professional and personal legacy includes the dozens of postdocs, graduate students, and undergraduate student researchers she mentored, as well as the hundreds of undergraduates she taught in her Evolution and Animal Behavior courses. The students and postdocs whose lives she touched were helped to be better scientists, but more importantly were inspired to be better people. She will be dearly missed by the many students and colleagues who will remember her as not only an exceptional scientist, but more importantly as a true friend.

2. From David Hibbett, Chair of the Biology Department at Clark University.

Professor Susan Adlai Foster and Research Professor John Allen Baker, Biology Department

Memorial Minute

October 27, 2021

Susan Foster passed away in January, 2021, followed less than five months later by her husband and collaborator, John Baker. Both were larger-than-life figures on the campus of Clark University, outgoing, engaging, and wildly popular with students. Their professional achievements were significant. Susan was an evolutionary biologist and ethologist. Her pioneering research using the threespine stickleback helped establish this diminutive fish as a premier model system for vertebrate biology. Among other accomplishments, Susan was President of the Animal Behavior Society, Landry University Professor of Clark University, and a National Science Foundation Presidential Faculty Fellow. She served as Chair of the Biology Department from 2006 to 2016.

John worked closely with Susan on stickleback research, including numerous field trips to Alaska with their students and postdoctoral fellows, but he had his own interests in ichthyology, conservation, and biodiversity of streams and rivers. For example, one of his last publications was on population genetics of the freshwater pearl mussel in New England. John was one of Clark’s most beloved teachers. His most popular classes included BIOL 101 - Introductory Biology and BIOL 084 – Biodiversity. Both routinely enrolled far above their caps. The last time John taught BIOL 101, in Fall 2019, there were 202 students. In 2013 John received the Teacher of the Year Award.

Susan and John came to Clark from the University of Arkansas in 1995. Over the next 25 years, they helped to revitalize the graduate and undergraduate programs in Biology, and they were central to the establishment and growth of the Environmental Science Program. But Susan and John did far more than teach classes and run programs; they created a community. The Foster-Baker universe had two centers, one in their laboratory in the Lasry Bioscience building and the other in their 250-year-old farmhouse in Petersham, where Susan died. Both were gathering places for students, family, friends, and colleagues, although the boundaries between those groups were often vague. Susan and John created possibilities, for learning, discovery, and second chances. They represented the best of Clark’s ideals, inspired fierce loyalty, and will be sorely missed

3. From Bill Cresko to his lab members

Susan Foster passed away yesterday due a rapidly progressing cancer that was only diagnosed early in 2020. She was able to be at home in Petersham MA with her husband and lifetime research partner John Baker, as well as her children Dylan and Patrick. Susan loved her colonial-era home and garden with the snow and the fireplace and the after seminar parties and the pickling of vegetables. Susan was my and Cristin’s Ph.D. advisor. She has been a professor of biology and the chair of the Biology Department at Clark University for much of the past decade, and retired in early 2020 at the first diagnosis. Susan advised numerous postdoctoral scholars, graduate students, and undergraduates over the years.

Susan was a pioneer. After her Ph.D. on Wrasse behavior at the University of Washington with Bob Paine, she did her postdoctoral work with Mike Bell at SUNY Stony Brook. In fact, I came to work with Susan after contacting Bob and telling him about my interests and he said ‘you should work with Susan instead on this amazing system’. At Stony Brook Susan helped develop the stickleback systems in British Columbia and Alaska, and through many publications helped biologists appreciate that behavior - like morphological and life history traits - could exhibit significant geographic variation that was influenced by both environmental and genetic variation. In addition to her many journal articles, Susan published two books with Mike Bell and John Endler that are now classics in the field.

Susan was a leader and role model in the fields of ethology and behavior. She help several leadership positions in the Animal Behavior Society, and she was part of an early wave of women in biology fighting for gender equity in the life sciences. Susan was a fierce advocate throughout her career for achieving the goal of having people judged by their abilities, not their chromosomal composition, skin color, or socioeconomic background. She matched these professional efforts at equity and inclusion in her private life in ways that were truly inspiring. The impacts that Susan has had on the field through her students from these diverse backgrounds (including me) is deep and broad.

In December of 2020 David Hibbett and others from Clark University and I began making plans for a virtual conference to honor the work of Susan and John. Unfortunately Susan’s cancer returned quickly at the beginning of the new year. We will continue our work to highlight Susan’s and John’s life work and educational legacy. All of you who are or have been in my lab working on stickleback have Susan to thank, and I hope that you will be able to attend.

Sincerely, Bill

4. From Jun Kitano - email to Andrew Hendry

This

sad news reminds me of my old days in Kyoto, when I came to know a series of

Susan Foster’s excellent works on behavioral variation in natural populations

of the threespine stickleback. When I almost finished my PhD thesis on

molecular neuroscience in mice, I was wondering what to do next as a postdoc. I

read several papers and books and finally found that I want to study wild

animals rather than laboratory mouse. One day, I came across a paper by Katie

Peichel, David Kingsley and their colleagues (Peichel et al. 2001 Nature). In

that paper, they investigated the genetic architecture underlying morphological

variation in the threespine stickleback. I thought that I could apply the same

genetic method to behavioral variation.

Then, I started to read many papers on the behavioral variation in sticklebacks, including those by Dr. Susan Foster. She has conducted extensive field observations and characterized behavioral variation in natural populations of the threespine stickleback. A series of her papers were so exciting that I perhaps spent more time reading her papers than reading papers directly related to my thesis. Reading her papers, I was convinced that behavioral genetics in sticklebacks would be an exciting direction of research. As I decided to work on Japanese populations in collaboration with Dr. Seiichi Mori (my long-term collaborator), I had no chance to work with Susan. But, Susan is definitely one of the persons who guided me into the stickleback research.

I met Susan at a stickleback conference in Alaska, and she kindly encouraged me. She invited me to her research fields in Alaska, although it did not happen due to several reasons. It is sad that we can no longer meet her, but her works will continue to encourage not only me but also many present and future young researchers. This would be a good timing to appreciate that our recent cutting edge genomic studies are based on the extensive works done by old researchers who spent a lot of time observing nature like Susan.

R.I.P.

5. From Jeff McKinnon - email to Andrew Hendry

I ran into Susan at various

times over the years. My fondest memory was visiting her and John at their

beautiful old house in Mass, probably in the early 2000’s. I remember their

generous hospitality and lively conversations about stickleback biology, as

well as about hockey. Susan was a great fan of Steve Yzerman, if memory serves.

6. From Tom Reimchen - email to Andrew Hendry

Gone before her time. As well as her obvious contributions to behavioural evolution in stickleback, another substantial contribution of Susan was her novel observations on coral reef fishes , particularly the importance of cleaning stations for the repair of wounds in coral reef fish (Foster 1985, Copeia 875-880). I have used this in my Ichthyology courses for many years as an example of co-evolution at a community level and as one of the first examples of self-medication in fishes.

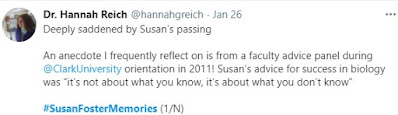

7. #SusanFosterMemories